Posted by Al Voth on 2023 Apr 13th

Rangefinders: Testing Beam Divergence And Reticle Alignment - Inside MDT

In my opinion, the laser rangefinder has been the single most important technical contribution to accurate long-range shooting. The first laser was built in 1960, with the term being an acronym for "Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation." A laser differs from other light sources in that it emits light coherently. This spatial coherence allows a laser to be focused on a tight spot and keeps it from spreading as widely as, for example, a flashlight beam. Laser beams are sent out as pulses for many applications, such as rangefinders. Along with the ability to transmit a laser pulse, a laser rangefinder can detect the reflected pulse's return. The instrument measures the length of time from sending to receiving and calculates the object's distance based on the time differential.

Fresh batteries and clean lenses will help any rangefinder perform to its maximum potential.

LASER RANGEFINDER BEAM DIVERGENCE

To understand lasers, it's important to realize that although visible laser beams appear to stay tightly and uniformly focused over their entire length, they "widen" as distance increases. This is called beam divergence; of course, they have much less divergence than the flashlight example mentioned earlier. However, not all lasers are created equally, and some devices have less beam divergence than others. Unfortunately, I don't know of any reliable way for the consumer to test beam divergence, so we're stuck with taking manufacturers at their word.

When you do look at beam divergence numbers, be aware they are usually expressed as an angular measurement in milliradians. Using the metric system and adjusting your scope in "mils," you'll be comfortable understanding these numbers. For imperial shooters using "minutes-of-angle," milliradians are just the metric version of minutes. And, of course, smaller is better when it comes to laser rangefinders. Some manufacturers report beam divergence as a rectangular shape, as in the Leica CRF 2800B: Vertical – 1.28 x Horizontal - 0.85 milliradians. Others report numbers that suggest a circular shape, as in the Leupold RX 2800: 1.172 milliradians.

The laser "beam" of all rangefinders widens as distance increases.

So, how much divergence is this really at distance? To simplify, let's assume a round beam with a divergence of 1.2 milliradians (which converts to 0.068755° if you prefer). The metric system makes the math easy because 1 milliradian is exactly 1 meter wide at 1000 meters, meaning our beam is 1.2 meters wide (47.24 inches) at 1000 meters (1094 yds). Most people don't realize their rangefinder's beam is about four ft. wide at that extended distance.

TESTING YOUR RETICLE AND BEAM ALIGNMENT

While I don't know of any method for consumers to test beam divergence, we can test a rangefinder to determine if the reticle and the beam are properly aligned. Sometimes they aren't, and if that's the case, you'll miss ranging a target just as surely as you'll miss a rifle shot if your riflescope isn't zeroed. All rangefinders have a reticle that must be superimposed on the target when the ranging button is activated. In a properly aligned device, the laser beam will strike the center of the reticle. But as we all know, no company's quality control is perfect, and even if a device leaves the factory properly aligned, there's no guarantee it'll stay that way. This makes it prudent to check your rangefinder at the start of every season.

Fortunately, it's easy. The only hard part is holding your rangefinder extremely still while ranging. Over the years, I have found that mounting your rangefinder on a tripod can be very steady. Another option is to stack up some sandbags and wedge your rangefinder tightly while leaving enough room to operate the controls.

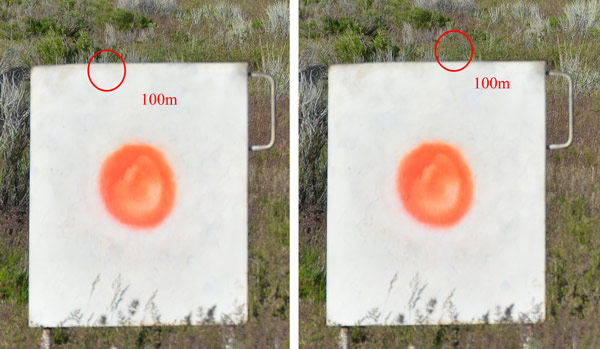

Start by ranging either a large steel target or the target backer at the 100-meter line and noting the distance. Then move the reticle to the top of the target and range the top edge several times, pushing the reticle closer to being "off" the edge each time. As you break over the edge, you should see the distance reading change to reflect the distance to the berm or whatever else is behind the target. You'll recognize a problem if, for example, the reticle is off the target and the distance to the target is still what's being displayed. This tells you where the beam is striking in relation to the reticle.

Slowly moving a rangefinder's reticle off the edge of a target frame makes it possible to determine if the reticle and beam are in alignment.

After testing on the top edge of the target, run the same test on the bottom edge. Then left and right edges as well. If your range has 200 or 300-meter target frames, consider also checking at one of those distances. Hopefully, the results will all be good. If they aren't, your best alternative is to contact the manufacturer for assistance in repair or replacement. If you can't get the necessary service, it's possible to adjust your point of measurement on a target to compensate for the beam/reticle alignment error.

LASER SAFETY

Fortunately, the lasers we use in hunting and shooting sports are safe. In the world of lasers, they are low-powered, and there's no risk of cutting or burning anything with one of these beams. They are classified as "relatively eye safe." However, we should never point any of the laser-equipped gear we use at a person. It's not worth the risk. Something to note, the military and law enforcement have access to high-powered lasers, and should you come across one at a range, or an event, do not point these lasers at someone since they can cause eye injuries.

OPTICS RESOURCES FROM MDT

- Red Dot Sights on Precision Rifles

- Optics: Understanding The Optical Triangle

- How to Zero a Rifle

- Tips for Cold Weather Shooting

- Scope Levels: Take your shooting to the next LEVEL

- Red dots on Precision Rifles

- How To Test Your New Riflescope

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Al Voth calls himself a "student of the gun." Retired from a 35-year career in law enforcement, including nine years on an Emergency Response Team, he now works as an editor, freelance writer, and photographer, in addition to keeping active as a consultant in the field he most recently left behind—forensic firearm examination. He is a court-qualified expert in that forensic discipline, having worked in that capacity in three countries. These days, when he's not working, you'll likely find him hunting varmints and predators (the 4-legged variety).

EUR

EUR

Canadian Dollars

Canadian Dollars